Η τέχνη της κινηματογράφησης - the Art of Cinematography

- Thread starter Kosh

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Technical scene breakdown: Outdoor night scene in "Heimsuchung"

Austrian thriller "Heimsuchung" ends with a night scene in a sunflower field. We interview the DP and gaffer to find out how they shot it.

- 26 March 2008

- 5,502

Art of the Cut: Killers of the Flower Moon | BorisFX

Today on Art of the Cut, it’s my pleasure to speak with legendary editor Thelma Schoonmaker, ACE, about working with her legendary director, Martin Scorsese, about their latest film, “Killers of the Flower Moon.”

borisfx.com

'Oppenheimer' Cinematographer Urges Filmmakers to Shoot on Analog in Oscars Speech

'It makes things looks so much better.'

κοντρα στο πνευμα και τις εξελιξεις της εποχης του δηλωνει και παροτρυνει να τραβουν φιλμ.

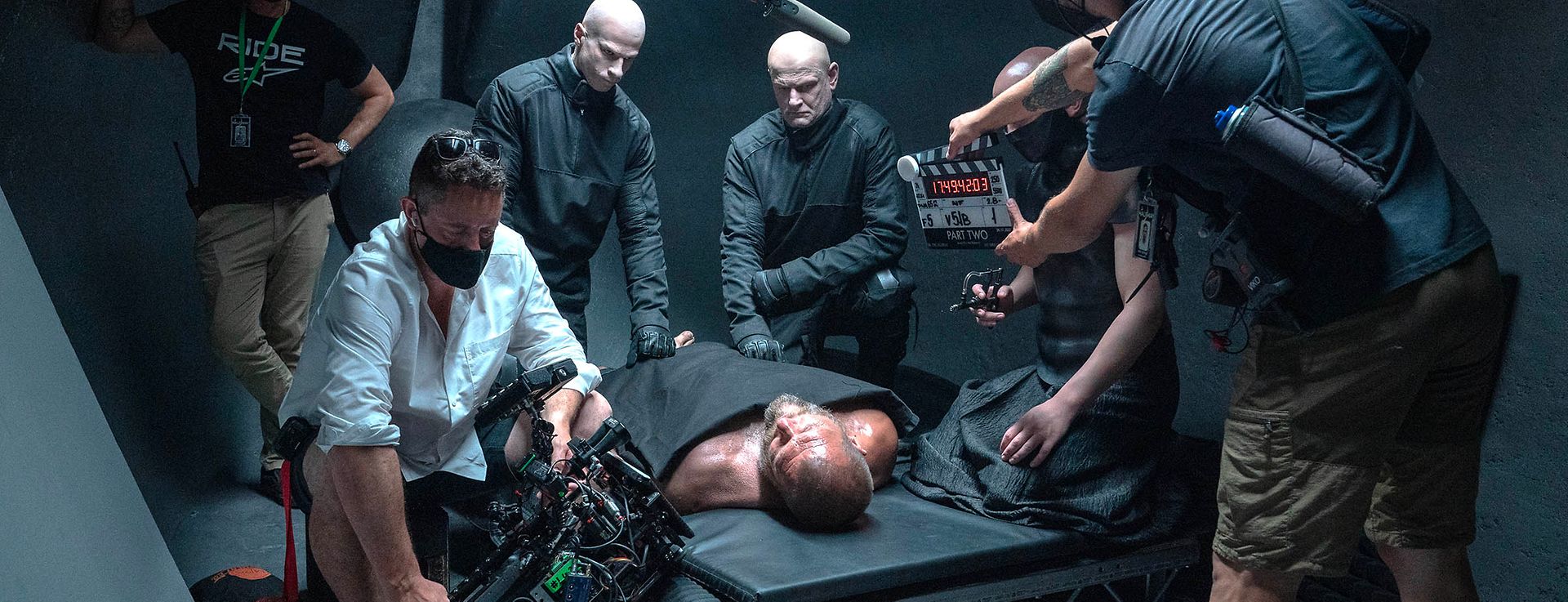

'Dune: Part Two' Was Shot Using Vintage Soviet Photo Lenses

The legendary Soviet-era Helios 44 continues to leave a lasting mark on cinema.

Among the most notable vintage lenses used to film Dune: Part Two is a Helios 44, a Russian-made clone of the famed Zeiss Biotar. With its distinctive 13-blade aperture diaphragm, the Helios 44, a 58mm f/2 prime lens, delivers unique and incredible bokeh.

“Wide open, it’s by far the softest lens I’ve ever owned — it has significant vignetting, terrible sunstars, and the corners are nothing to write home about. However, regardless of its downsides, it has quickly become my all-time favorite lens,” Mark O. wrote for PetaPixel in 2020.

If this lens is so soft, how was it used to shoot what could be the highest-grossing film of 2024?

Arri Rental explains that Fraser elected to shoot Dune: Part Two entirely with spherical — not anamorphic — lenses. Working directly with Arri Rental, Fraser selected some remarkable lenses from the famed camera and lens maker.

“I worked closely with Christoph Hoffsten at Arri Rental in Germany to tune and detune optics. The Moviecams were pleasing and had good depth, as well as a really good range to choose from. They helped create the texture I wanted, and the Soviet glass was especially well suited to what we were doing; we used them all in harmony, effectively,” Fraser explains.

The award-winning cinematographer cites the resolution and fidelity of Arri’s largest Alexa image sensors as an occasional problem rather than a universal benefit, saying that “we needed to dirty the image up a bit.”

Dune unit photographer Chiabella James told PetaPixel last year that Fraser has a rich background in stills photography, which James said helped her create a strong bond with the cinematographer and led to a lot of fantastic photography conversation on set.

IronGlass Adapters’ Soviet Rehoused MKII Set | Credit: IronGlass Adapters

According to Kosmo Foto, the Soviet lenses Fraser used came from Ukrainian company IronGlass Adapters. This outfit converts old Soviet lenses, like the Helios 44, Mir-20, Mir-1, and Jupiter-9 85mm portrait prime, for use on modern camera systems.

“The development of this body and the mechanics began in 2021, in early 2022, the next prototypes were produced, and then there was war… Despite the difficult times, the team continued to work, some on the ground, some remotely from the trenches. Really glad we got the pre series irons done for Greig Fraser in time and he took full advantage of them on the Dune set,” IronGlass Adapters’ Kostiantyn Harkavyi wrote on Facebook last weekend.

“It pleases me that among thousands of other variants, the MKll from IronGlass was chosen, that they did a great job without complaining about the mechanics and optical composition, that even in difficult times in a war country we can make a world-class quality product and be involved in bright movie events. So we continue to work hard so you can enjoy a brilliant movie.”

Arri’s Alex 65 camera system may be too sharp for Fraser’s taste in some cases, but the large format cinematic camera system also opens up many creative possibilities for lenses.

“What I love about 65 mm is that it removes restrictions for me, opening up so many more lens options. You can work with lenses originally designed for smaller formats, where you see parts of the glass that were never intended to be seen. For me, seeing and feeling those hidden parts is an eye-opener, literally and figuratively. It helps me dirty up the image and give it texture in ways you couldn’t do with a smaller format,” Fraser explains.

Interview on "Dune: Part Two" with Greig Fraser ACS, ASC

ALEXA 65, ALEXA Mini LF, and lenses including exclusive ARRI Rental optics chosen by cinematographer Greig Fraser for the second part of director Denis Villeneuve's epic sci-fi adaptation.

A tale of two formats

A critical early decision for Villeneuve and Fraser was whether and how to alter their visual approach to the first film for the second. "Dune" was shot in full-frame large format with ALEXA LF and Mini LF cameras. Knowing that the IMAX release would allow for aspect ratio changes at different points in the film, Fraser shot certain parts of the story in 2.39:1 with anamorphic lenses and other parts with spherical lenses so they could be shown in 1.43:1 to fill the IMAX screen. The second film would also be a 'Filmed for IMAX' title, but that didn't mean they had to make exactly the same equipment choices.Fraser recalls, "We started by asking ourselves some philosophical questions about whether part two needed to look the same as part one. Do we continue with the same format? Do we stay with digital, or do we go to film? Do we shoot 16 mm? It's a bigger world that we're building in part two; there are more planets, more set pieces, and more action. We decided to keep the fundamental through-line of large-sensor ALEXA cameras, but to combine ALEXA 65 with ALEXA Mini LF and shoot the whole thing spherical. That kept our options open for the IMAX version and we felt that 65 mm with the Mini LF was a good combo."

Eclectic lenses

Having decided to shoot entirely with spherical optics, Fraser investigated lens options in collaboration with ARRI Rental, eventually opting for a diverse selection. From ARRI Rental's exclusive offerings, he chose re-housed 1980s Moviecams, combining them with re-housed Soviet-era glass supplied by IronGlass and some of his own lenses. He says, "I worked closely with Christoph Hoffsten at ARRI Rental in Germany to tune and detune optics. The Moviecams were pleasing and had good depth, as well as a really good range to choose from. They helped create the texture I wanted, and the Soviet glass was especially well suited to what we were doing; we used them all in harmony, effectively."Texturizing the image was the name of the game," says Fraser. "The larger ALEXA sensors are so extraordinary that I felt we needed to dirty the image up a bit." To help achieve this, ARRI Rental provided the cinematographer with additional lenses from its HEROES collection, designed to deliver extreme looks. Fraser continues, "We had a 57 mm LOOK lens with Petzval glass where you can dial in your effect with a third lens ring, and a 50 mm T.ONE lens. They were incredible, although we didn't end up using them as much as I'd intended because our focal lengths were more in the longer range, but I'm hoping to incorporate them on another movie, especially if ARRI Rental makes more of them."

Infrared black and white

Intrigued by infrared cinematography ever since experimenting with it on "Zero Dark Thirty" a decade earlier, Fraser turned to the idea when considering how to shoot scenes set on the planet Giedi Prime. He says, "We'd been on this planet for night interiors in part one, but we'd never been outside, so we were discussing what it would look like. I did a test for Denis where the inhabitants have very pale white skin, based on the notion that there's no visible light from the sun on Giedi Prime, only infrared light. When the characters go from inside to outside, they effectively go from normal light to infrared light."The infrared images worked best in black and white, so that was the aesthetic choice made for Giedi Prime exteriors. ARRI Rental carries a limited number of native black-and-white ALEXA Monochrome cameras that can see into the infrared spectrum, but not enough were available for the shoot, so the IR filters were removed from regular ALEXAs for these scenes, with Fraser adding a filter in front of the lens to block almost all visible light from the sensor. Colors were desaturated to monochrome for on-set monitoring and postproduction.

Fraser says, "On 'Rogue One,' ARRI Rental modified some ALEXA 65s to do exactly the same thing, and we used them as VFX cameras, lighting parts of the set with IR light that didn't affect the main image. We just took that a step further and used them as our main cameras for Giedi Prime. They literally only record the infrared that bounces off skin or clothes, so colors are rendered as different tones and something that looks black to the eye might look white to the camera. It meant that we had to have exterior and interior versions of the same costume for some characters."

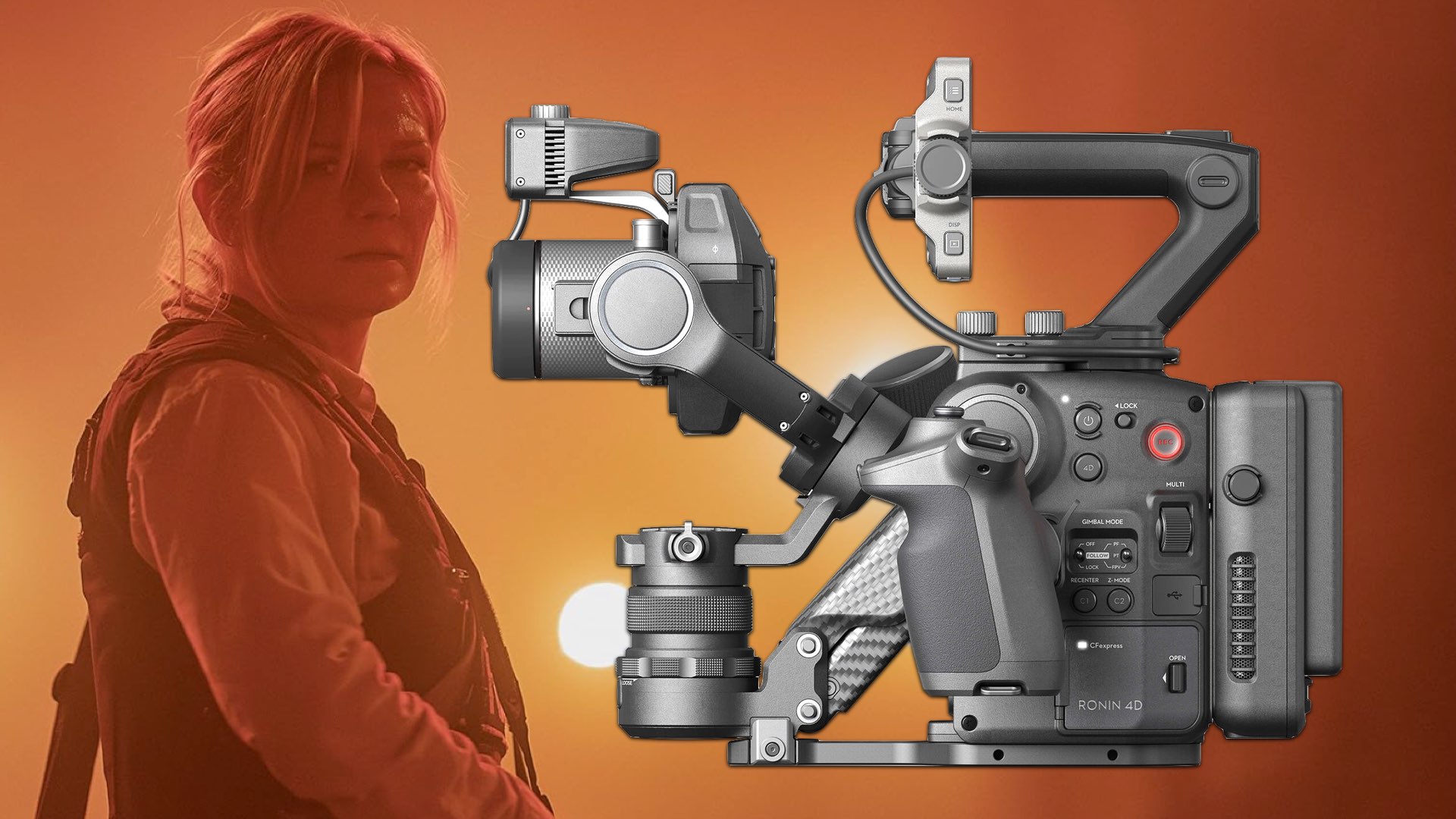

Civil War Cinematography: Ronin 4D 6K as the 'Invisible' Camera - Y.M.Cinema Magazine

In Civil War, the DJI Ronin 4D 6K was used to capture the middle of the action. It was defined by the actors as the 'Invisible' camera.

ymcinema.com

ymcinema.com

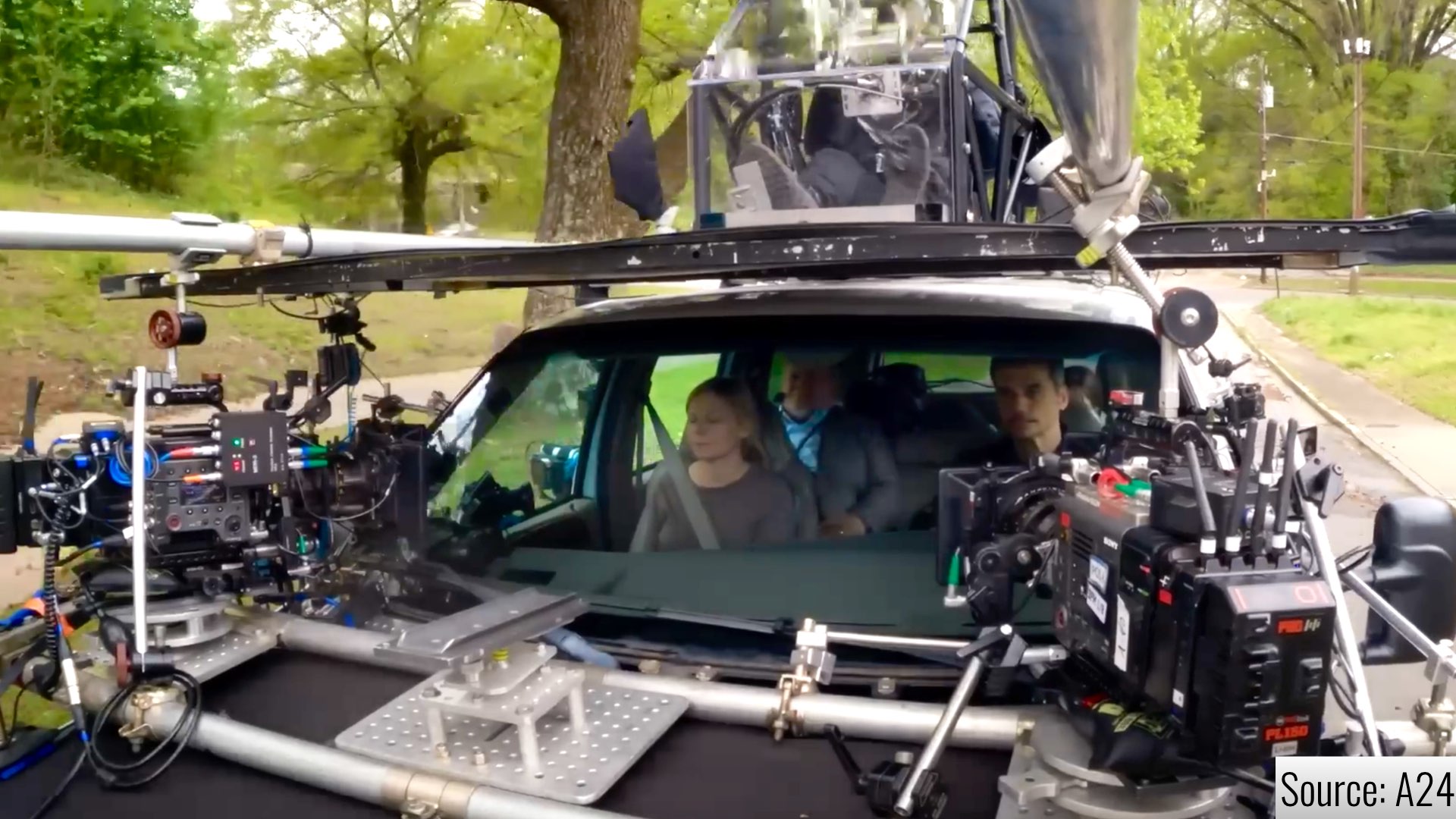

Ενα απο τα σεταπ/ rigs για το γυρισμα on the road της ταινιας.

The cinematographer behind the hit TV series Fallout has revealed how he created the epic visual style of the video game adaptation with lighting, color, and leaning into the Western genre.

Fallout has been among Prime Video’s most-watched series since it was released last month and has been praised as one of the best examples of the video game adaptation genre.

‘It’s Clean and Well-Photographed’

In an interview with Gold Derby, Fallout’s cinematographer Stuart Dryburg says he actually moved away from the original video game and leaned into the Western genre to create the cinematic look of the show.When Dryburg was first approached by Fallout director Jonathan Nolan to work on the series, the cinematographer naturally looked for inspiration in the original video game.

“I looked at some of the play-throughs of the game and made some assumptions about the [TV show] looking sort of treated and gamey,” Dryburgh tells Gold Derby as part of the publication’s Meet the Experts: Cinematographers panel.

“I even pulled a whole bunch of visuals from Pinterest to support the idea.”

However, when Dryburgh met with Nolan, most of his initial research was rejected for a “clean and well-photographed” aesthetic favored by the Western genre.

“Jonathan said, ‘Yeah, those are all very interesting, but, no, we’re not doing it like that,’” Dryburgh, who was nominated for an Academy Award for his cinematography on the 1993 film The Piano, says.

“His tastes are much more straightforward in terms of screen storytelling. And if you take a look at Westworld [created by Nolan] as an example, it’s a very clean look.

“It leans into the idea of the Western a bit, but visually it’s clean and well-photographed. And that’s ultimately what we did with Fallout”

Inventing Lighting

In a further interview with IndieWire, Dryburg says he was impressed by the sheer scope of the original Fallout video game in terms of atmosphere, settings, locations, and characters.However, he felt that the lighting was not a key part of the visual design and something that he would have to largely invent for the television series.

“It’s a good-looking game, but not cinematic in a lighting sense,” Dryburg tells IndieWire.

As he began conceptualizing the show, Dryburgh’s guiding principle was to give each of the central locations its own look — with each place requiring “a distinct color palette and atmosphere.”

Dryburgh worked with Fallout production designer Howard Cummings to give the vault set a lighting style similar to that of a 1950s supermarket, which was big on fluorescent fixtures built into the set.

“Essentially, we wanted the vault to be lit by the practical sources,” Dryburgh tells the publication, explaining that it gave him great flexibility with his camera.

“We could run all over without worrying about where lights might have to be hidden.”

Locations and Shooting on Film

IndieWire reports that Dryburgh employed totally different textures for the other major locations in the TV series.The scenes set in the “Brotherhood of Steel” headquarters were filmed largely in Utah and Dryburg “used a lot of cyan tones and picked up off the neutral grays and whites of the salt flats” while shooting there. Meanwhile, the scenes in the Wasteland were partly shot in Namibia where “it’s very orange, very parched, and very brown.”

As well as extensive location work, Dryburg says that key scenes were shot on LED volumes with screens that extended the sets — a situation that was made more challenging for Dryburgh by shooting on film.

“It’s so much easier on digital — what you see is what you get,” Dryburg tells IndieWire.

“With film, you’ve got to make sure you’re exposing it at the right color temperature for the screens to interact with your foreground elements. It’s like, could you find a harder way to do it? But it looked great. The results speak for themselves.”